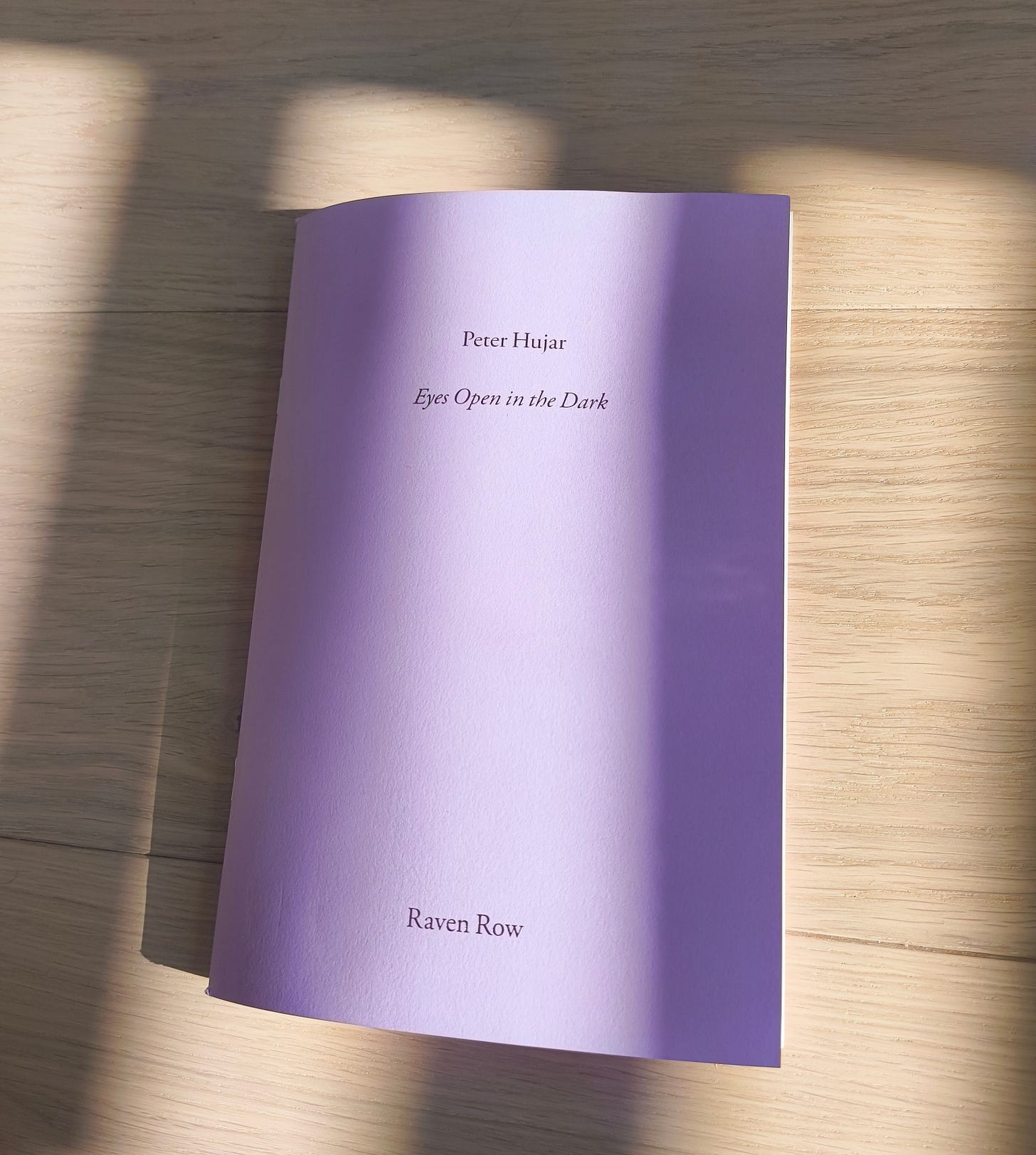

Peter Hujar – Eyes Open in the Dark

30 January – 6 April, 2025

Maybe you know it already, maybe you don’t. If you haven’t been before, Raven Row is tucked away in those funny little lanes near Liverpool Street just off Spitalfields. It’s that oddjob bit of the City where the tourists hunting out viral grilled cheese pulls in the market get sandwiched up between all the bankers, lawyers, and East Anglian commuters.

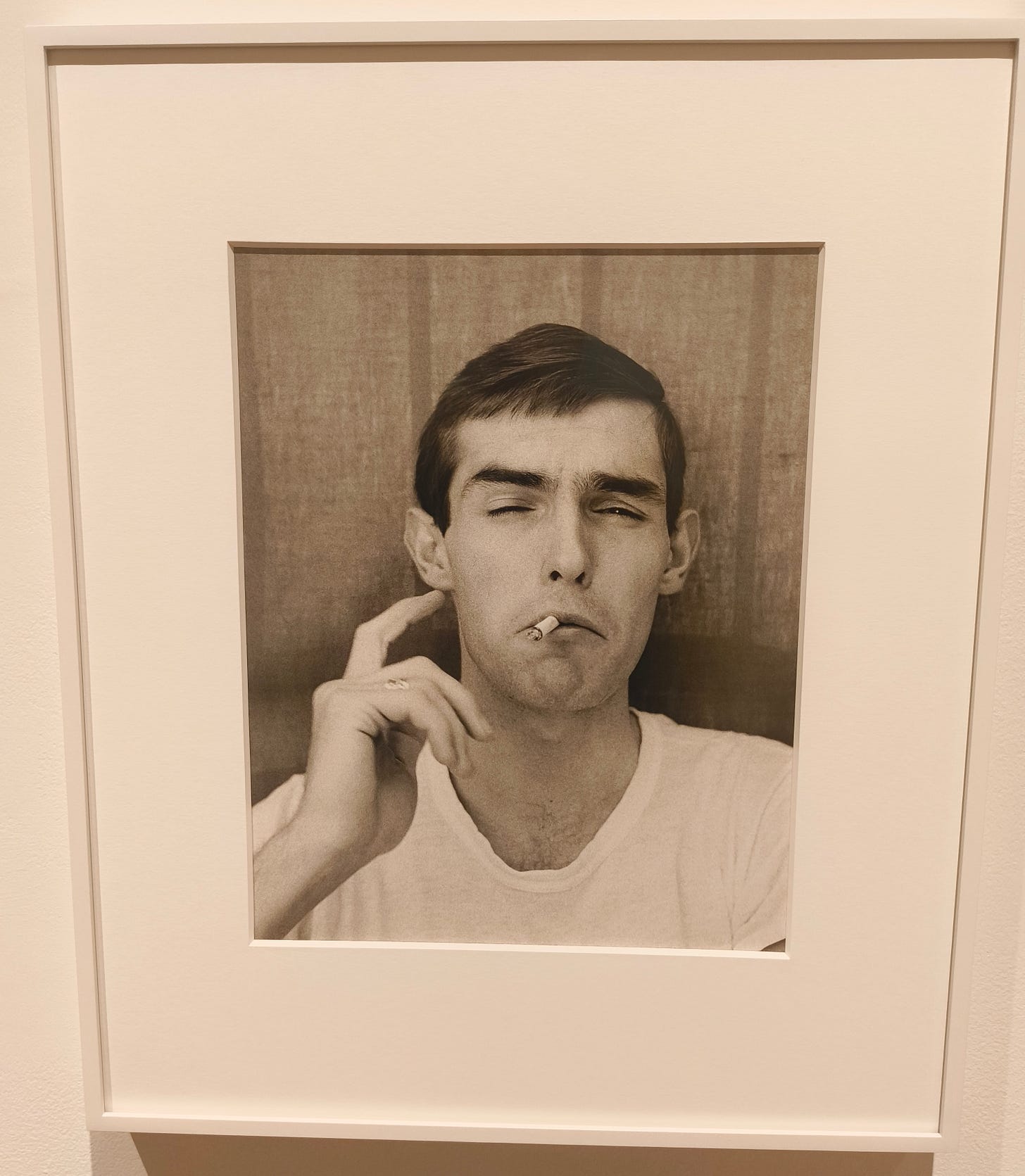

Maybe you also know Peter Hujar already, maybe you don’t. Hujar is now a very well regarded photographer, but was (and himself felt) underknown in his lifetime, beyond the NYC scene. This new show in London provides a pretty unmissable overview of some of his most vital work, as both a celebration and an epitaph of sorts.

The show is accompanied by a superb free publication featuring a series of essays and interviews. Inside it, some of those who knew Hujar best capture something of the intricacies of a character who was both cantankerous and charming, argumentative and alluring. But the images in the show – many of them printed by his friend and mentee Gary Schneider (who writes brilliantly on the process) – are of course what’s most important.

They tell the story of a photographer, who, while working in black and white, expresses an almost technicolour range and a fiery talent. The downstairs galleries at Raven Row are devoted to a wide-ranging look at mostly New York work from the mid-70s to the end of his life in 1987.

It’s tough not to reach for comparisons sometimes. Avedon was one of his collectors, and you can see something of both him and Irving Penn in Hujars’s still life of a stiletto, shot in lavish tones with a glistening, but self-aware delight.

And, I hesitate to mention Robert Mapplethorpe at all here. Yes they were contemporaries, yes they died two years apart as victims of the same epidemic, yes they shot black and white work of many of the same people and subjects. But there’s a kind of cold obsessiveness present in Mapplethorpe’s work that is absent in Hujar’s.

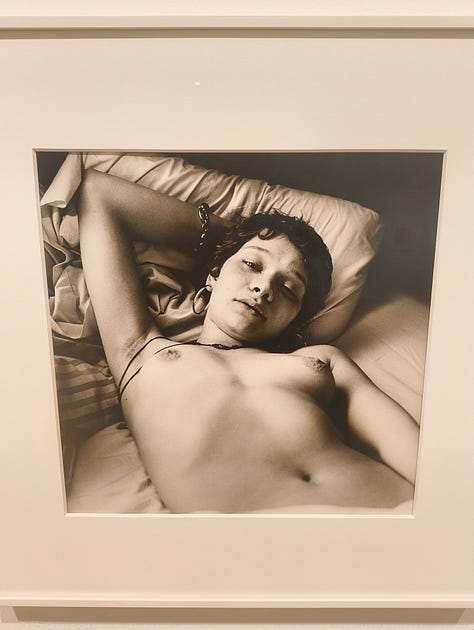

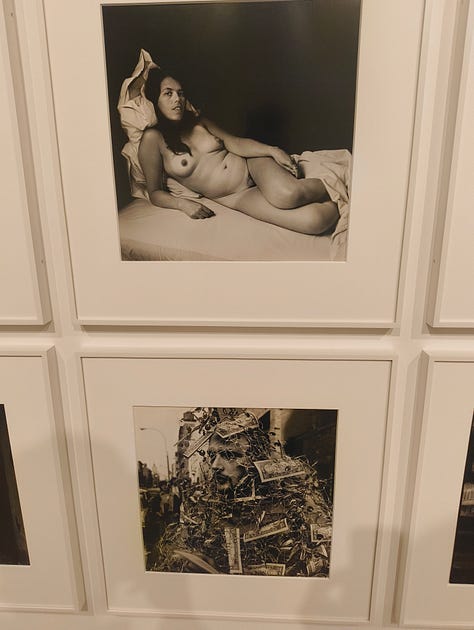

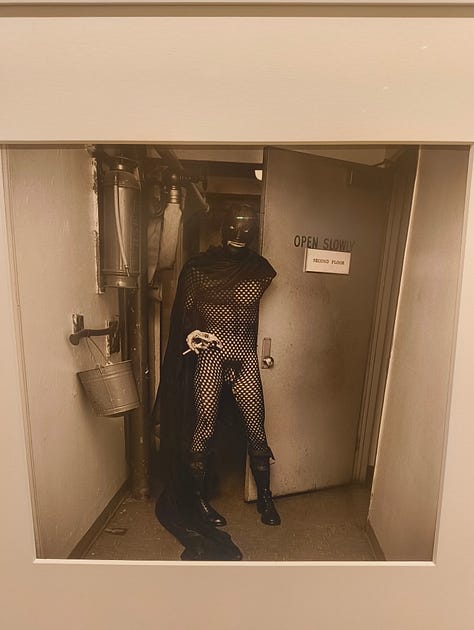

Hujar is Hujar though. He captures the baroque and the bizarre while never falling into the trap of treating it as a freakshow. In part, perhaps this is because his most extreme images (a portrait of his own asshole, or another of the artist squatting to insert a large sex toy into said orifice) feature himself as both subject and object. While it’s never sentimental, it still feels strangely soft (well, apparently not that dildo).

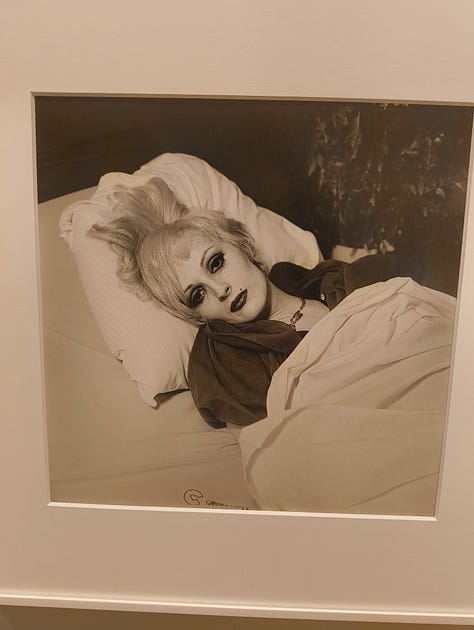

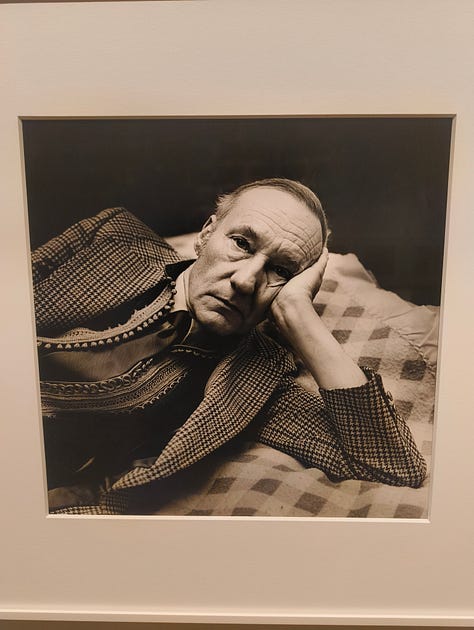

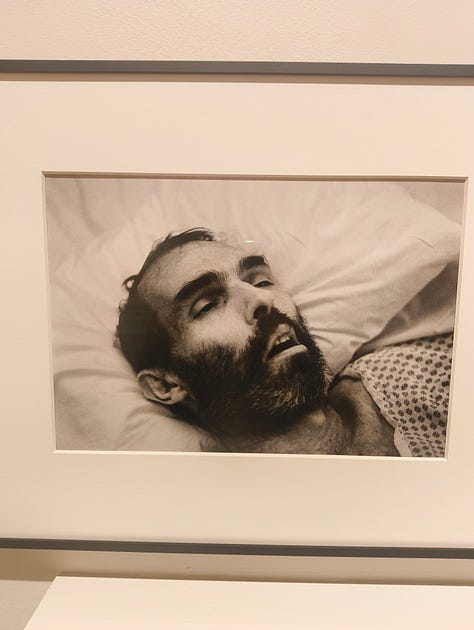

There’s plenty of celeb spotting in this section – William Burroughs, Susan Sontag, Fran Lebowitz et al. And the now iconic image, ‘Candy Darling on her Deathbed’, is here too. It’s interesting that it’s often mistakenly treated as a relic of the AIDS crisis, but it was taken when she was dying of lymphoma aged 29 in 1974. There’s a wider scope of tragedy and beauty at play here.

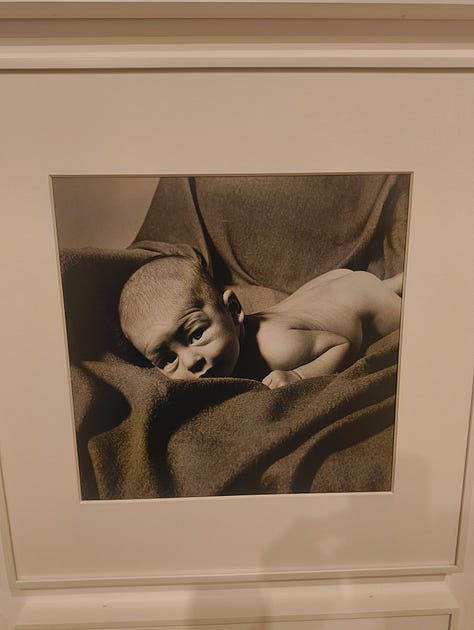

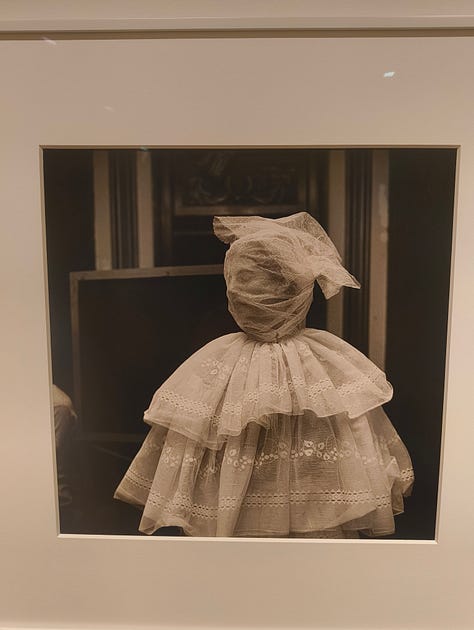

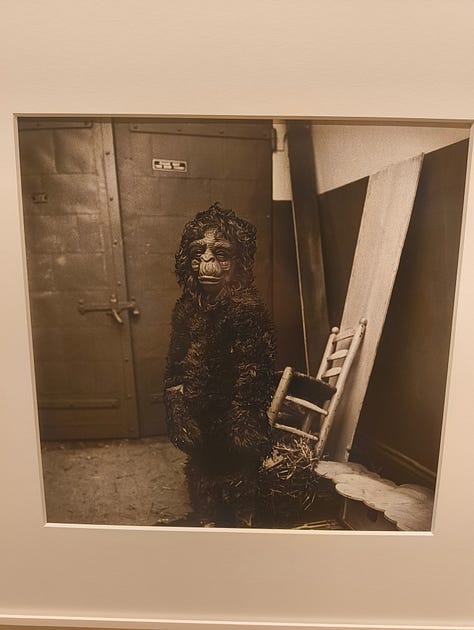

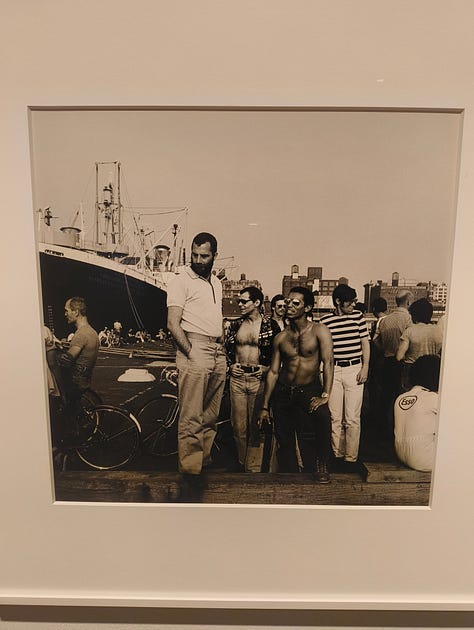

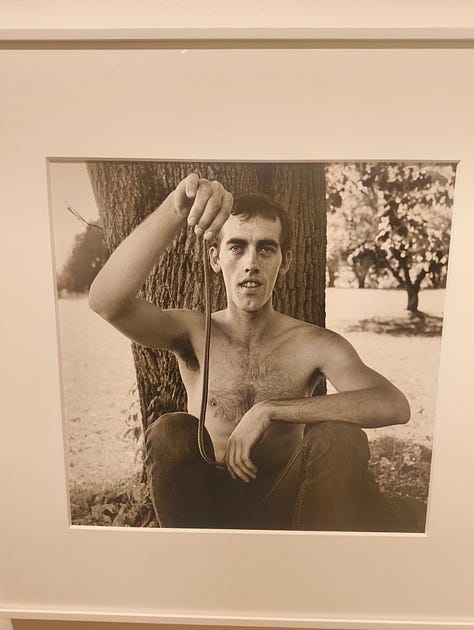

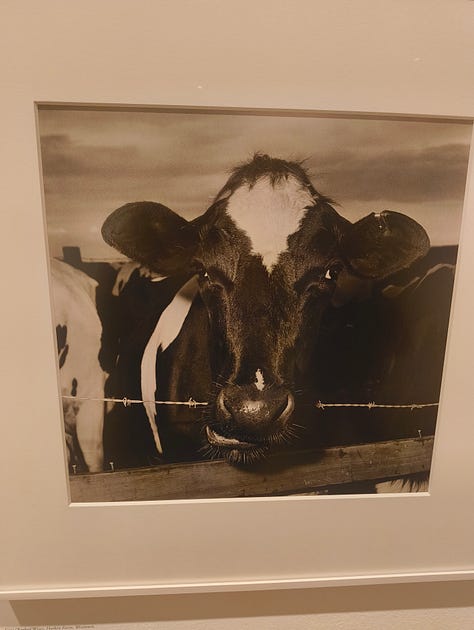

The exhibition explores some of Hujar’s expressively stark urban landscapes, and shows off a tender rawness in his images of animals (horses, dogs, donkeys, cows etc). And if he could be irascible with people, he obviously also coaxed out something unparalleled when they sat or posed for him. He shoots the raucous, sensual joys of cruising at the Christopher Street Pier. He shoots gentle baby portraiture. He shoots both homeless transwomen and famous writers like old friends. He shoots bizarrely becostumed performers backstage in bright flashlight. He shoots abandoned buildings. All of it with an eye you couldn’t always call ‘warm’, but which always seems focused on the sensitivities of the human and the humane.

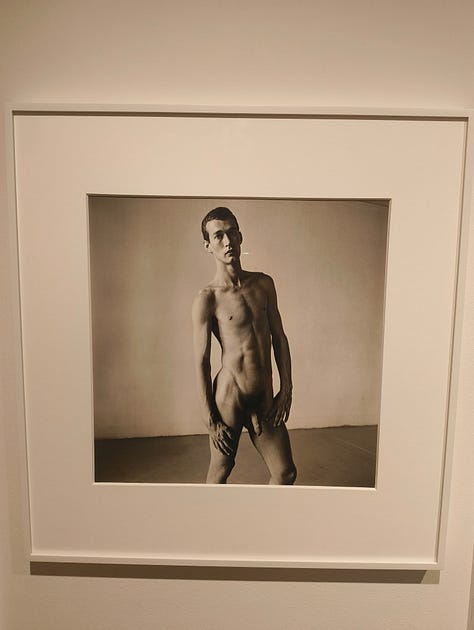

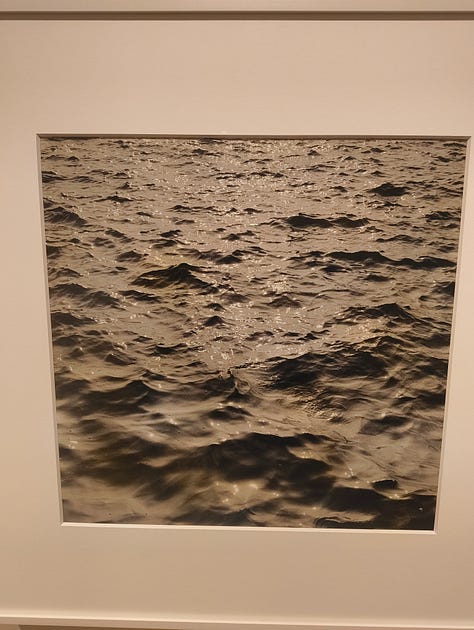

Upstairs is a focus on work from one year, 1976. One subject is dancer, and later AIDS archivist Bruce de Sainte Croix, who survived 12 years with the disease between diagnosis and the availability of effective drug cocktails to control it. He’s shot seated, nude, angelically lit, with his eyes fixed contemplatively on his own erect penis. If it feels too holy for pornography, ostensibly too pornographic to be holy, it’s because it pulls at the threads of those terms. That same year he also shot a series of images of the Hudson river for a chapel at Fordham University, and they hang just next door like evocative topographies, mountainscapes in small squares of moving water.

The photographs taken by his friend and sometimes lover, the artist and writer David Wojnarowicz, of Hujar’s body in the moments just after his death from AIDS on Thanksgiving 1987, provide a heart-wrenching testament to both the person, and the medical, social, artistic, and political catastrophe that stole so many lives.

This is a truly brilliant show, packed with images that slowly invite you to feel, as much as to look. It’s one not to miss.